Introduction

Plantation was originally a group of settlers or a governmental unit established by them during British colonization, particularly in North America and the West Indies, as described by the International Labour Organization(1). This paper explores the condition of tea plantation workers starting from West Bengal and stretching to the southern side. We shall commence with a brief history of tea plantations. Tea plantation workforce comprises more than 50 per cent workers as women. Many of Indias tea plantation workers are concentrated in the state of Assam, where they remain physically and economically isolated(2). Historically, women have made up a majority of the workforce, but their contributions to trade unions are dubious. The causes would include low literacy rates and patriarchal mind-sets, which still plague many people(3). The tea business holds the nearly unusual distinction of having succeeded in maintaining a downward spiral and this disadvantaged position generation after generation. The tea sector is the most marginalised in terms of politics, society, and the economy(4). “The most important and valuable… on matters connected with the agricultural or commercial resources of this empire,” was announced by the British India Tea Committee on December 24, 1834. Until they learned that tea could be cultivated in upper Assam, botanists thought that China was the only place where tea was naturally grown. This finding gave rise to idealistic imperial ideas. For the British, being free of the costly Chinese tea and canton trade was the main source of leisure(5). This, along with other factors, started tea plantation in India and a system of imprisoning generations of workers.

History Of Tea Plantation

The demand for tea, and consequently Indias production of it, was greatly influenced by the industrial revolution and urbanisation in England. While many people now consider tea to be a daily necessity, historically it was an expensive, luxurious beverage that was only produced and served to the elite. Following that, it was well-liked and considered to be an everyday need for the working class in England. Despite the fact that tea used to be viewed as an ‘exotic luxury’, by 1730, tax concessions and increased commerce with China had rendered tea cost-effective for nearly everyone(6).

The development and prosperity of the Indian tea industry was aided by a number of factors, including the high demand for Indian tea, the lack of competition from other foreign or Indian planters, the inexpensive nature of land for gardens, the extremely low initial capital requirement, cheap labour, the slim technical requirements, and public patronage(7).

China-imported tea plants were used to create the first tea estates in Assam. Since tea plantation was quite a labour-intensive work, Brits staffed slaves for the plantation. Fortunately, slavery was outlawed in the British Empire in 1833, to combat such The East India Company’s found a substitute. Tea estates used men and women who signed contracts requiring them to work for a set amount of time as indentured labourers rather than slaves. In actuality, though, these labourer’s circumstances weren’t all that distinct from those of slaves(8).

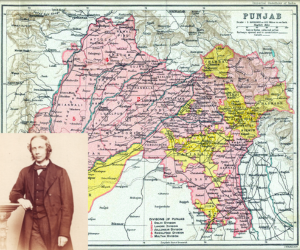

Darjeeling was recognised by the British East India Company as an ideal location for tea cultivation. Darjeeling’s soil and environment were ideal for the growing of tea leaves. Darjeeling plantations were commonly preferred over Assamese ones due to the superior quality of odour in their black teas(9).

The Britishers came up with The Sardari system to compact the regular labour obstacles, which saw individual gardens send Sardars to hire labourers once a year in exchange for a recruiting incentive of Rs. 10 per person. Nepal and Sikkim were both home to cheap labour. Every year, each garden used to send Sardars to Sikkim and Nepal in order to recruit labour during the winter months, which usually started in October or November after the rains and lasted till February. This hiring procedure was the most efficient and least expensive method of bringing in workers. The British strengthened this system by advocating for families to be

employed instead of individuals, so they brought the entire family(10).

The approach of employing the entire family proved to be more cost-efficient since it allowed planters to assign wages per family, which was considerably cheaper than assigning wages per individual. Also, these workers were separated from their homeland, which prevented their return back to their homeland. All family members—men, women, and children—were given distinct jobs, and this family-based employment allowed the planters to have a competent and regimented labour pool of workers. Males were given jobs such as digging and smothering the plants with insecticides and herbicides, considered tough tasks. On the contrary, women were given gentle tasks such as plucking, supplying manures, splitting the soil, and setting up nursery beds. Wages given to them were considerably low, in 1866, men labourers received a monthly wage of five rupees while female labourers were given 4 rupees per month. Because the owners were hesitant to bear the hefty expenditures of creating a suitable labour settlement, living conditions were poor. Workers basic needs were disregarded, and there was a generalised nutritional deficit among them. This resulted in stomatitis in both male and female workers, and in certain severe cases, it even killed them. In addition, women did not receive adequate maternity leave, which increased the rate of stillbirths. Furthermore, in five Assamese districts in 1918, there were 113 recorded stillbirths compared to 569 live births(11).

Oppressive and exploitative practices were used by the proprietors of tea plantations, despite the harshness, migrant labourers from all over the nation saw the employment as a great opportunity. The absence of labour movement despite extreme deprivation by the owners was a significant contributing factor to the seamless operation of the tea plantation. Since they were outsiders and considered low in caste, workers were not able to garner support fromothers in order to protest against this kind of injustice. As a result, the colonial-era tea garden owners exploitative practices regarding the hiring and working conditions of labourers were not confronted(12).

West Bengal Tea Workers

The states tea belt is home to about 302 tea gardens, each covering 200–1,200 acres. A government estimate puts the number of people who work in the tea gardens at close to 3 lakh, primarily tribal people who speak Nepali. Yet their voices remain unheard(13).

A) Wage

Darjeeling, sometimes referred to as the champagne of teas, has the most beautiful tea gardens on earth, what lies beneath the beauty is the brutal reality of the tea plantation. Women are significantly disadvantaged in this situation due to the double burden of low incomes and domestic duties. Men, in the hopes of earning higher salaries, have begun moving to larger cities and villages. As a result, women must maintain an equilibrium between domestic duties and their tedious, low-paying jobs(14). As the workforce declined they put substantial amount of pressure on businesses to raise employee wages from Rs 45 per day in 2000 to Rs+ 202 per day in 2021. However, the circumstances of those who labour on tea plantations remain miserable. Although what might appear to be an increase in pay, workers still cannot afford wholesome food or access to healthcare due to price increases in commodities(15). From 2014 to 2023, West Bengals wages climbed by just 9.28% (16), the previous year saw a jump in the daily income of these workers from 232 to 250 rupees (17)

Tea plantation labour wages were anticipated to be set using a standard minimum wage formula that was agreed upon by all parties at the 15th Indian Labour Conference (ILC) in 1957. The meeting came to the conclusion that a needs-based minimum wage needs to be set in accordance with the minimal requirements of three consumption units, taking into account an individual’s basic needs for food, clothes, and shelter. Three and a half years following the ILC’s ruling, in 1960, the pay board for the tea plantation business was established. Given that employment on plantations was family-based—that is, men, women, and children

worked together—the employers fiercely opposed the basis for wage fixing as three units of consumption. They claimed that three units would mean a much higher wage than the minimum needs, and their argument wasn’t backed by a discussion with the labourers. The board regrettably decided to arbitrarily oppose the three consumption units, which was later agreed by the board. The explanation provided by the board was that they were unable to recommend wages that would be in line with the current cost of living and the need-based wage formula established by the 15th Indian Labour Conference(18).

Prior to the enactment of the Equal Remuneration Act, 1976 female workers received 17 paisa less in pay than their male counterparts. This act aimed to eliminate wage differentials against women and aimed to work to protect women from job discrimination and achieve equal pay for equal effort. Employers were against the enactment of the act, their reasoning was that if women were to get equal pay, then both male and female plantation workers should perform equivalent tasks. Post enactment of the act, consequently, the planters unwaveringly adhered to the incentive wage plan, which enhanced the female employees workload and the business owners earnings. Another effect of the act post its enactment was that the act has caused casual workers to replace permanent women workers, the Equal

Remuneration Act (ERA), 1976, hence failed to protect the rights and interests of women in the plantation industry(19). Abhijit Majumdar, member of the Siliguri Welfare Organisation, defines the situation of ‘perpetual famine’ that has become prevalent over time in North Bengal’s shuttered or neglected tea farms. He further held and blamed the management’s total apathy and the bleak salary structure for the workers extreme poverty(20).

The Plantations Act, 1951, which is applicable to all states except the smallest ones, is the main labour law that governs these workers. Owners are required by the statute to supply housing, healthcare, education, and other amenities. In addition, tea estate workers are protected under the Industrial Disputes Act of 1947, the Payment of Gratuity Act of 1972, the Payment of Wages Act of 1936, and other laws since they are employed in the formal sector. Nonetheless, employers have taken advantage of the rise of contract and casual labourers to circumvent these regulations(21). According to a survey conducted by the West Bengal Network

on the Right to Food and Work, employers have neglected to deposit workers dues with the provident fund commissioner since 1997. Thousands of crores of rupees were involved in this. According to the legislation, employers that fail to deposit their employees provident contribution—which is withheld from their wages—should face criminal charges. In reality, this is equivalent to wage fraud for the workers. However, the state did not bring any criminal charges(22).

b) Living and Working Conditions of Tea Plantation Labourers

Workers in the Darjeeling hills plantations are originally from Nepal, where they were duped into claiming their families were guaranteed greater opportunities. Studies on the living and working conditions of tea plantation labourers reveal that conditions have been poor for labourers since the middle of the 19th century(23). The planters and management reason their inadequate wages by contending that social advantages including housing, healthcare, education, subsidised rations, water supply, free land for farming, and firewood are given to the workers. However, the Plantation Labour Act of 1951 makes these benefits mandatory. The advantages of the law are accessible for male workers spouses, minor children, and senior dependents; but, in the event of a female worker, the benefits are limited to the worker and her kids. This makes for a blatant violation of gender equality(24). To further elucidate, the fact that the definition of dependents varies for male and female workers highlights the existence of prejudice based on gender. Wife and parents who do not work are regarded as

dependents for men in the workforce. Parents and a non-working partner are not regarded as dependents for female employees. Men’s ration entitlements would therefore be more than women’s for a given family size(25).

A new housing scheme was launched in West Bengal in 2022 for tea plantation labourers, called Chaa Sundari. Tea garden labourers will receive housing under the parja patta (land document) rights as part of the scheme. An analysis carried out in 2022 by a labour trade union showed that the scheme can eventually make their lives worse by raising their cost of living. The single feature of the newly designed homes is a cooking gas provision, which raises living expenses by at least Rs 1,150 in order to obtain cooking gas, adding 20% to total costs. Neither is the Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (PMUY) available. The workers have contended that even half of the sum allocated to the project for existing houses would be sufficient to repair them and allow them to live comfortably, despite the fact that Rs 5.43 lakh has been set aside per unit(26). In addition, because the homes are made of tin sheets, they become overheated in the intense summer heat and the people are forced to go outside. Lack of open space outside for raising cattle, which is a vital component of their livelihood and helps to augment their pitiful earnings, is another growing problem. In addition, the families worry about what will happen to their residence once the designated household member retires or if no one else in the family decides to take up the tea garden work. There is uncertainty on whether the family would have to vacate the house or not(27).

These women are subjected to horrible living conditions and are severely underpaid. In accordance with a fact-finding mission assessment, tea workers in India are qualified for maternity allowance under the Plantation Act, 1951, but they are not entitled to the minimum 14-week leave stipulated in Article 4 of the ILO Maternity Protection Convention (2000). Temporary workers there lack even this basic need, which is a gross violation of international and national laws(28).

c) Health Conditions of Labourers

A study was conducted among which, 463 tea-garden labourers from the marginalised group in West Bengals Alipurduar district—the majority of whom were female and illiterate—were the study participants. 22% percent had hypertension, and 57% had pre-hypertension, 24.2% suffered from a few non-communicable illnesses. Anaemia affected as many as 87.9% of the workers in the tea gardens. Morbidity, observed to be fairly common, affected 69.8% of study participants overall. Non-communicable diseases, musculoskeletal disorders, skin issues, respiratory disorders, feverish illness, ocular morbidities, vitamin and micronutrient

deficiency disorders, worm infestation, and other conditions were prevalent among the tea- garden workers (29).

Another study that involved 122 tea workers from seven different tea farms revealed that nutritional deficiencies were a big worry. Just 48 responders BMIs fell between 18.5 and 24.9, which is considered a normal weight range. Of the remaining workers, 44 had a BMI of less than 17, indicating a significant nutrient deficiency, and the rest workers were underweight. It is true that BMI is not the only indicator of health but according to World Health Organisation criteria, using a numerical scale ranging from 17 to 30, BMI is an essential tool for evaluating the relation of weight to height. It allows individuals to be categorised into four groups: underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese(30).

There are also several instances of starvation deaths in the area. The survey’s lead researcher, renowned pediatrician and public health specialist Dr. Binayak Sen, claims that one major factor contributing to the region’s chronic hunger deaths is the availability of food and nutrition, both of which are severely compromised in these communities by a lack of a variety of nutrient-dense food options and inadequate sanitation. None of them have access to drinking water, bathrooms, or even subsidies for their food(31).

Pursuant to a 2012 state-government assessment, over 1,000 people passed away from malnutrition in West Bengals 273 tea plantations since 2002. Another study in 2005 by the West Bengal Agriculture Workers Association found that malnutrition affects almost 75% of the kids residing on plantations(32).

Assam Tea Workers

Neighbouring Bengal comes another state famous for its tea but at the cost of thousands of lives, stuck in the loop of plantation because of lack of alternative. The British kept their labourers in what was known as ‘Lines’, which were made up of rows of shacks next to a tea garden with common restrooms. The living and working conditions of the tea tribes were no less than torture, which included frequent physical attacks, a system of middlemen and recruitment agents (Sardar) who exploited their inferiors, and no way out of this form of indentured labour. The conditions were strikingly similar to those of the slaves who were kept in the American South’s cotton plantations, but the people there were able to free themselves from this bondage. I n Assam, life has hardly improved since then(33).

a) Wages

During the colonial times, the Hazira and Tickca comprised the two halves of the Assam tea estates system. The employee obtained his hazira (daily payment) by accomplishing the regularly assigned assignment. After performing his Hazira, if the worker volunteered to perform another obligation, he would be awarded what was known as his ticca upon fulfilling that supplementary task. The earnings from wages comprised both ticca and hazira(34).

The workers could barely make the ends meet. But the planters and the Brits were adamant in their view that they had given adequate wages. Their justification for injustice inflicted was that “coolie indolence” would rise if “coolies” (informal word used then for unskilled workers) received greater earnings—that is, wages above what the planters regarded as subsistence level. The British, while having tea in their elegant mansions, said that the wages are not only adequate for the coolie to support himself with nourishment, clothing, and a few comforts, but he also works hard to earn sufficient funds to spend freely on gambling, drinking, and cockfighting when he has extra money(35).

Presently, in an effort to get paid more, hundreds of female plantation workers from the Sealkotee tea estate in the Dibrugarh area went to protest. The adoption of a minimum wage of Rs 351 per day for tea plantation workers was one of the demonstrators main demands. They asked management to take immediate action, claiming that their present daily compensation of Rupees 250 was not insufficient to satisfy their most fundamental needs (36)

Parliamentary Standing Committee report from 2022 stated, “The terrible living and working conditions of tea labourers are reminiscent of the indentured labour introduced in colonial times by British planters”. But major rectification steps have not been taken so far. The Assamese tea workers daily wages climbed by a meagre Rs 27 in 2022. Even yet, this was a huge difference in pay from what plantation workers in the southern states were paid. In addition to compensation, as stipulated by the Plantation Act and other labour statutes, tea plantation workers are also entitled to benefits like paid time off (PF), gratuities, housing, free medical care, free education for their children, gasoline, and protective gear like raincoats, high boots, aprons, and crèches for female employees. These are currently limited to paper. All of these rights have continuously been violated; nonetheless, it is uncommon for

plantation workers to receive these rights. This is especially true for tea plantation workers(37).

Management deductions are also made from the inadequate wage. According to an Oxfam India survey, plantation workers pay is decreased by their employers on average by ₹778 every month. In reality, the labourer was paid between ₹160 and ₹180 per day. Deductions were made for the Assam Chah Mazdoor Sangha (ACMS) membership fee, provident fund, and other categories(38).

Similar to their Bengali counterparts, the low pay rate poses a significant obstacle to their upward trajectory, with the majority of tea garden labourers putting in 8 to 10 hours a day at a pitiful wage. The most significant obstacle for tea garden labourers in Assam is the issue of unawareness, their world is restricted to tea gardens. It has a direct connection to a lack of education. Due to this as a direct consequence, they are deprived of access to several resources, including insurance, credit options, self-help groups, and many more advantages. Another lingering issue is of child labour. Other significant disadvantages for tea garden workers include teenage marriage. They struggle to provide for their enormous family(39).

b) Living and Working Conditions of Tea Plantation Labourers

Women described their appalling working conditions and claimed that there were no latrines or hand-washing facilities available to them. Consequently, there was absolutely nothing to do but defecate in the plantation regions. The lack of a facility at work for changing sanitary pads or clothes during menstruation made things more challenging. Ladies wore clothing that they laundered and then reused. During lunch break at a private plantation, women would return home to change into menstruation-absorbent clothes. However, amid all the misery Women told stories of how, while picking leaves, they sang songs and shared each others joys and sorrows. Despite the atrocities that they are exposed to every day at work, they are content and laugh, sing, and share one others suffering(40).

Despite the fact that the Factories Act of 1948 and the Plantations Labour Act of 1951 have enough provisions to guarantee tea garden workers a minimal level of housing, health, and safety, the rules are frequently disregarded or unenforced. The majority of plantation labourers live in one-room homes, with their big families. The chemicals used on plantation estates expose many women to health problems, and there is simply no medical support available to help. Even during the monsoon season, tea picking continued, which created extremely challenging working conditions because there was insufficient cover for lunch breaks and a risk of accidents due to slick, rainy roads. The monsoon poses another challenge which is insect bites while working(41).

c) Health Conditions of Labourers

The plantations lack basic sanitary facilities and access to clean drinking water. Just that infringes upon fundamental rights, as The Indian Supreme Court has upheld the right to water as a fundamental human right, derived from the right to life secured by Article 21 of the constitution (42) . However, these workers are ignored. Numerous investigations have revealed that the quality of drinking water is low, and the majority of plantations lack running water, drinking water, or toilets—a major contributing factor to kidney stones in labourers(43).

Another issue is with the medical facilities provided. Women expressed dissatisfaction with the quality of care they received at the hospitals on each plantation they visited, regarding the medical services promised by the Plantation Act. One of the main causes of this discontent was that physicians in plantation hospitals were not always available and the workers had to travel to district hospitals. Permanent workers said that whereas male permanent workers spouses and children were eligible for health care on plantations, female employees husbands were not. Consequently, the medical expenses incurred by non-full-time employed husbands constituted an extra financial burden (44)

Assamese tea is traditionally consumed in the field with salt and pepper, according to activist Sanjay Bansal. This tradition has persisted for many years in Assams tea estates. Since its inception during British control, estate owners have adhered to this custom. The proprietors gave out large quantities of salt-laden tea to treat extreme dehydration brought on by extended workdays in the sun and heat. The custom persisted, leading to a high salt intake among employees, which in turn caused the majority of them to have high blood pressure(45).

Yet another instance of poor sanitation that lingers around is neurocysticercosis (NCC). Assam’s tea workers are one of the state’s most marginalised with unsafe working conditions, such is backed by a 2019 study by non-profit Oxfam (46) . They have low salaries, no access to basic facilities, and a high danger of human rights violations. Many plantation labourers, both

temporary and permanent, raise pigs as a supplement to their meagre earnings. Both labour and investment are minimal. The drawback, however, is that workers contract NCC, a disease that can be avoided but has a devastating effect on the pig-rearing communities of Assam. Cysts are created when the tapeworms eggs infiltrate human muscles. These cysts canvoccasionally penetrate peoples brains, resulting in migraines and epileptic convulsions. NCC has a long history of endemicity in Assam, it is only recently that they have been discovered, according to Dr. Bhagat Lal Dutta, an Assamese-based One Health epidemiologist. The solution is simple yet difficult to achieve, improved sanitation and hygiene would significantly lower the risk of NCC, as researched by the World Health Organisation. An extremely treatable disease will keep presenting an imminent danger to the lives and livelihoods of Assamese tea workers until their precarious living conditions change(47).

Families of tea workers consistently suffer from malnutrition and ill health. They suffered from skin sores, TB, meningitis, diarrhoea, and other ailments because they were compelled to live in an unsanitary environment. Furthermore, every time a worker sprays chemicals on bushes, the garden neglects to provide safety clothing and dungarees, leaving the bushes open to "serious side effects from chemical exposure". The Human Rights Institute at Columbia Law School is absolutely correct in stating that the Indian tea industry has ‘abusive conditions’ throughout(48).

The area also reported mushroom deaths. Workers resort to eating mushrooms to satisfy their hunger because the pay is so pitifully low that their families frequently go without food. Assam is dotted with wild mushrooms in March and April, which makes mushroom poisoning fatalities particularly common in the state (49).

Way Forward

The process of collective bargaining determines wages; yet, one of its shortcomings is that workers have relatively little bargaining power. White-collar officers, not actual workers, are the people who represent the labour market. Due to their lack of participation in the process, collective bargaining with asymmetrical negotiating power ultimately results in low wage realisation and a diminished voice for the workers. A potential remedy is seen in the southern region of India, where Minimum Wage Schedule notifies the wages twice a year. Tea workers pay ought to be disclosed as part of the Minimum Wage announcement. At the very least, a minimum wage would guarantee subsistence-level survival(50). Recent announcements of unilateral interim wage rises by the state governments of West Bengal and Assam have signalled progress in this area (51).

As previously indicated, tribal people who are kept separate from the indigenous population work on tea estates. They have never lived among the natives, having been recruited from outside, and since they were located close to the tea estates, they were not treated as a part of that community (52). The government has not given the welfare of tea workers the priority that it ought to have. The government came up with plans and promises, but their problems were never the main political objectives. One explanation for this may be because they are still viewed as outsiders(53). Therefore, raising awareness of the predicament faced by these workers

has to be a major concern and a hot topic of conversation. Given their lengthy history of suffering, it is important to actively defend their rights and to stop viewing them as outsiders.

These workers are prevented from pursuing other careers by the high rates of illiteracy among them. Under the Plantation Labour Act of 1951, the planter owner was previously solely responsible for guaranteeing schooling. In West Bengal, the state government took over management of the schools housed within the plantations later in the 1990s. Transportation is a big challenge for their secondary education and further studies because they live distant from urban areas(54). Government assistance is also required in this scenario. Government priority should be given to constructing institutions and secondary schools close to them. A fairer and more sustainable tea sector can be achieved by tackling issues like low pay, bettering working conditions, guaranteeing healthcare and social security access, doing away with exploitative tactics, and encouraging education and skill development. Prioritising the

rights and well-being of tea garden labourers is essential if we are to ensure that everyone has a prosperous and just future. 55 This might be accomplished by creating a distinct government agency to handle these issues. So that workers can go directly to labour law departments and fight for their rights, the government should establish direct connections between plantation workers and those offices(56).

Conclusion

The workers in tea gardens are subject to nine labour and social welfare laws. However, as long as the federal and state governments are unwilling to go above and beyond simply passing scrutiny on each other and placing the blame on the other, they will remain merely pieces of legislation, and neither the execution of current laws nor the introduction of new ones will ever improve(57). The lack of concern shown by northern plantation management for its workers is a well-known reality. It is troubling that they show such blatant contempt for the ILO conventions standard for decent work. Thus, state government intervention becomes

absolutely necessary(58).

Footnote

- Bhowmik, Sharit K. “Ethnicity and Isolation: Marginalization of Tea Plantation Workers.” Race/Ethnicity:

Multidisciplinary Global Contexts, vol. 4, no. 2, 2011, pp. 235–53. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2979/racethmulglocon.4.2.235, accessed 20 Mach. 2024. - “Expanding Access to Justice through Community-Based Paralegals in New Delhi and Assam – the REACH Alliance” (The Reach Alliance, January 3, 2023) https://reachalliance.org/case-study/expanding-access-to- justice-through-nazdeek/, accessed 20 Mach. 2024.

- Kanchan Sarkar, and Sharit K. Bhowmik. “Trade Unions and Women Workers in Tea Plantations.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 33, no. 52, 1998, pp. L50–52. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4407515, accessed 21 Mach 2024.

- GOTHOSKAR, SUJATA. “This Chāy Is Bitter: Exploitative Relations in the Tea Industry.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 47, no. 50, 2012, pp. 33–40. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41720464, accessed 22 March 2024.

- Sharma, Jayeeta. “‘Lazy’ Natives, Coolie Labour, and the Assam Tea Industry.” Modern Asian Studies, vol. 43, no. 6, 2009, pp. 1287–324. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40285014, accessed 22 March 2024.

- Nayantara Arora, “Chai as a Colonial Creation: The British Empire’s Cultivation of Tea as a Popular Taste and Habit among South Asians” (2022) 21 Oregon Undergraduate Research Journal 9 https://doi.org/10.5399/uo/ourj/21.1.7, accessed on 20 March 2024.

- Misra, Bhubanes. “Quality, Investment and International Competitiveness: Indian Tea Industry, 1880-1910.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 22, no. 6, 1987, pp. 230–38. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4376649. Accessed 20 March 2024.

- Rowlatt BJ, “The Dark History behind India and the UK’s Favourite Drink” (BBC News, July 15, 2016) https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-36781368, accessed on 20 March 2024.

- Nayantara Arora, “Chai as a Colonial Creation: The British Empire’s Cultivation of Tea as a Popular Taste and Habit among South Asians” (2022) 21 Oregon Undergraduate Research Journal 9 https://doi.org/10.5399/uo/ourj/21.1.7, accessed on 20 March 2024.

- Sadia Akhtar and Wei Song, “British Colonization and Development of Black Tea Industry in India: A Case Study of Darjeeling” (2021) 10 Advances in Historical Studies 215 https://doi.org/10.4236/ahs.2021.104014, accessed on 20 March 2024.

- “Exploitation of Tea-Plantation Workers in Colonial Bengal and Assam” (2015) 2 Mr. Aritra De 277 <https://oaji.net/articles/2015/1115-1449212453.pdf>, accessed on 21 March 2024.

- Ibid.

- Atri Mitra , Ravik Bhattacharya,” In Bengal’s tea belt an unsavoury brew — lack of jobs, land issues and migration”, The Indian Express,(April 18, 2024), https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/kolkata/in-bengals- tea-belt-lack-of-job-hope-leads-to-workers-migration-9276813/, accessed on June 15, 2024.

- “Steeping in Struggle: The Plight of Tea Plantation Workers in Darjeeling – TCI” TCI, (February 10, 2023) <https://tci.cornell.edu/?blog=steeping-in-struggle-the-plight-of-tea-plantation-workers-in-darjeeling>, accessed on 21 March 2024.

- “Why Bengal Tea Workers Feel Let down by Political Parties” Down to Earth, <https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/governance/why-bengal-tea-workers-feel-let-down-by-political- parties-76424>, accessed on 21 March 2024.

- Tea industry issues hold key in north Bengal polls, The Economic Times, (April 11, 2024),https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/elections/lok-sabha/west-bengal/tea-industry-issues- hold-key-in-north-bengal-polls/articleshow/109214516.cms?from=mdr, accessed on June 14, 2024.

- Tea minimum wage in limbo after meeting, Telegraph India (Jan. 10, 2024), https://www.telegraphindia.com/west-bengal/minimum-wage-of-tea-garden-workers-in-limbo-after-18th- meeting-of-advisory-committee/cid/1992696, accessed on 14 June 2024.18 SELVARAJ, M. S., and SHANKAR GOPALAKRISHNAN. “Nightmares of an Agricultural Capitalist Economy: Tea Plantation Workers in the Nilgiris.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 51, no. 18, 2016, pp. 107–13. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44004242, accessed 20 March 2024.

- SELVARAJ, M. S., and SHANKAR GOPALAKRISHNAN. “Nightmares of an Agricultural Capitalist Economy: Tea Plantation Workers in the Nilgiris.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 51, no. 18, 2016, pp. 107–13. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44004242, accessed 20 March 2024.

- Mamta Gurung and Sanchari Roy Mukherjee, “Gender, Women and Work in the Tea Plantation: A Case Study of Darjeeling Hills” (2018) 61 The Indian Journal of Labour Economics 537 <https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027- 018-0142-3>, accessed on 21 March 2024.

- “Tea Gardens in the East Are Brewing Starvation, Malnutrition” (The Wire), <https://thewire.in/economy/tea-gardens-in-the-east-are-brewing-starvation-malnutrition>, accessed on 21 March 2024.

- SELVARAJ, M. S., and SHANKAR GOPALAKRISHNAN. “Nightmares of an Agricultural Capitalist Economy: Tea Plantation Workers in the Nilgiris.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 51, no. 18, 2016, pp. 107–13. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44004242, accessed 21 March 2024.

- BHOWMIK, SHARIT K. “Living Conditions of Tea Plantation Workers.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 50, no. 46/47, 2015, pp. 29–32. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44002859. Accessed 21 March 2024.

- Ibid.

- Mamta Gurung and Sanchari Roy Mukherjee, “Gender, Women and Work in the Tea Plantation: A Case Study of Darjeeling Hills” (2018) 61 The Indian Journal of Labour Economics 537 <https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027- 018-0142-3>, accessed on 21 March 2024.

- Kingshuk Sarkar, Low wages and Gender Discrimination: The Case of Plantation Workers in West Bengal, V.V. Giri National Labour Institute,(2019), https://vvgnli.gov.in/sites/default/files/136-2019-Kingshuk_Sarkar.pdf.

- “Labour Union Raises Concerns over Housing Scheme for Bengal Tea Workers”, Down to earth, <https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/governance/labour-union-raises-concerns-over-housing-scheme-for- bengal-tea-workers-87981>, accessed on 21 March 2024.

- Gurvinder Singh, “Tea Garden Workers Face Bitter Home Truth in Bengal” (Village Square, August 10, 2023) <https://www.villagesquare.in/tea-garden-workers-housing-challenges-west-bengal/>, accessed on 21 March 2024.

- Nangsel, “Darjeeling: Women&#8217; Exploited Labour behind Our Cups of Tea” (Feminism in India, September 19, 2020) <https://feminisminindia.com/2020/02/17/darjeeling-womens-labour-tea/>, accessed on 21 March 2024.

- Yasmin, Shamima et al. “Poverty, undernutrition and morbidity: The untold story of tea-garden workers of Alipurduar district, West Bengal.” Journal of family medicine and primary care vol. 11,6 (2022): 2526-2531. doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1322_21, accessed on 21 March 2024.

- Himanshu Nitnaware,”Survey highlights severe nutrition deficiencies in West Bengal tea workers”. Down to Earth (April 16, 2024) https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/governance/survey-highlights-severe-nutrition- deficiencies-in-west-bengal-tea-workers-95586, accessed 14 June, 2024.

- “Tea Gardens in the East Are Brewing Starvation, Malnutrition” (The Wire), https://thewire.in/economy/tea- gardens-in-the-east-are-brewing-starvation-malnutrition, accessed on 21 March 2024.

- Ashutosh Shaktan, “The Plight of the Tea Plantation Workers of Dooars” (The Caravan, June 24, 2016) https://caravanmagazine.in/vantage/plight-tea-plantation-workers-dooars, accessed on 22 March 2024.

- Shivaji Das, “‘Everyone Wants to Leave but They Can’t’: The Lives of the Bagania, Tea Plantation Workers in Assam” Scroll.in (July 24, 2023) https://scroll.in/article/1052768/everyone-wants-to-leave-but-they-cant-the- lives-of-the-bagania-tea-plantation-workers-in-assam, accessed on 22 March 2024.

- Gupta, Ranajit Das. “From Peasants and Tribesmen to Plantation Workers: Colonial Captialism, Reproduction of Labour Power and Proletarianisation in North East India, 1850s to 1947.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 21, no. 4, 1986, pp. PE2–10. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4375248, accessed 22 March 2024.

- Ibid.

- Times Of India, “Plantation Workers Stage Stir, Seek Better Wages” The Times of India (February 21, 2024) https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/guwahati/plantation-workers-demand-better-wages-hundreds-of- female-workers-stage-stir/articleshow/107869331.cms, accessed 22 March 2024.

- “Tears beneath the Tea Cups!” (AICCTU) https://www.aicctu.org/index.php/workers-resistance/v1/workers- resistance-oct-2023/tears-beneath-tea-cups, accessed 23 March 2024.

- Rahul Karmakar, “Assam Tea Workers Get a Fourth of ‘Living Wage’: Study” (The Hindu, July 14, 2021) https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/other-states/assam-tea-workers-get-a-fourth-of-living-wage study/article35315619.ece, accessed 22 March 2024.

- Shivaji Das, “‘Everyone Wants to Leave but They Can’t’: The Lives of the Bagania, Tea Plantation Workers in Assam” Scroll.in (July 24, 2023) https://scroll.in/article/1052768/everyone-wants-to-leave-but-they-cant-the- lives-of-the-bagania-tea-plantation-workers-in-assam, accessed 22 March 2024.

- Preety R Rajbangshi and Devaki Nambiar, “‘Who Will Stand up for Us?’ The Social Determinants of Health of Women Tea Plantation Workers in India” (2020) 19 International Journal for Equity in Healthhttps://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-020-1147-3, accessed on 22 March 2024.

- “India’s Tea Gardens: Poor Conditions Persist” (British Safety Council India, September 12, 2022) https://www.britsafe.in/safety-management-news/2022/india-s-tea-gardens-poor-conditions-persist, accessed on 23 March 2024.

- Narmada Bachao Andolan v. Union of India, (2000) 10 SCC 664.

- Natalie Taylor, “The Silent Water Crisis behind India’s Most Precious Tea” The Third Pole (May 24, 2021) https://www.thethirdpole.net/en/pollution/tea-gardens-assam-silent-water-crisis/, accessed on 22 March 2024.

- Ibid.

- “Tea Gardens in the East Are Brewing Starvation, Malnutrition”, The Wire, https://thewire.in/economy/tea- gardens-in-the-east-are-brewing-starvation-malnutrition, accessed on 21 March 2024.

- “ADDRESSING THE HUMAN COST OF ASSAM TEA”, Oxfam, (October 2019), https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/620876/bp-human-cost-assam-tea- 101019-en.pdf, accessed on 22 March 2024.

- “Worms Thriving in Brains, Assam’s Tea Garden Workers Lose Lives, Livelihoods” https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/health/worms-thriving-in-brains-assam-s-tea-garden-workers-lose- lives-livelihoods-80630, accessed by 22 March 2024.

- Kunal Bose, “Working Conditions in Assam Tea Gardens Poor” www.business-standard.com (September 21, 2015) <https://www.business-standard.com/article/markets/working-conditions-in-assam-tea-gardens-poor- 115092200058_1.html>, accessed by 22 March 2024.

- “India’s Tea Gardens: Poor Conditions Persist”, British Safety Council India, (September 12, 2022) <https://www.britsafe.in/safety-management-news/2022/india-s-tea-gardens-poor-conditions-persist>, accessed on 23 March 2024.

- Kingshuk Sarkar,” Wages, Mobility and Labour Market Institutions in Tea Plantations: The Case of West Bengal and Assam”, NRPPD, Centre for Development Studies, Trivandrum (2015), https://cds.edu/wp content/uploads/2021/02/NRPPD46_Kingshuk.pdf, accessed on June 14, 2024.

- Dr. Kuriakose Mamkoottam, “Assessing the Need for Living Wage Benchmark Studies for the Tea Sector in Assam and West Bengal”, Anker Research Institute and ISEAL, (July 2023), https://www.globallivingwage.org/wpcontent/uploads/2023/09/ReportBenchmark_TeaAssam_WB_090823.p df, accessed on June 14, 2014.

- Supra note 50

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “Problems Faced by tea garden workers and Solutions”, Halmari Tea,(June 22, 2023),https://www.halmaritea.com/blog/problems-tea-garden-workers-solutions/, accessed on June 15, 2024.

- Tripti Panwar, ”Living Conditions of Tea Plantation Workers”, Volume 2, Issue 8, IJARND, (2017), https://www.ijarnd.com/manuscripts/v2i8/V2I8-1138.pdf.

- “Misery in the Tea Gardens: Tea Plantation Workers Face Starvation, Trafficking and Political Neglect.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 49, no. 38, 2014, pp. 9–9. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24480694,accessed 28 March 2024.

- BHOWMIK, SHARIT K. “Wages of Tea Plantation Workers: Gap between North and South.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 50, no. 19, 2015, pp. 18–20. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24482248, accessed 28 March 2024.